Darko Suvin

F.R.S.C. Emeritus, McGill University, Montréal QC, Canada [dsuvin@gmail.com, Lucca, Italy]

On the one hand, there have started into life industrial and scientific forces, which no epoch of the former human history had ever suspected. On the other hand, there exist symptoms of decay, far surpassing the horrors of the later times of the Roman Empire. In our days everything seems pregnant with its contrary.

Karl Marx, Speech at the Anniversary of the People’s Paper

Nun muss sich alles, alles ändern. [Now all, all has to change]

Ludwig Uhland, Frühlingsglaube [Spring Belief, also lied by Schubert]

When I was introducing the term and concept of the novum in 1977, I refunctioned it from Ernst Bloch’s philosophy of hope for science fiction (further SF) as well as for an age no longer facing Nazism. Both these reasons made for less stark choices and less teleology than in Bloch. To begin with, I associated the novum intuitively with novelty and innovation (Suvin “SF”). However, what may have been mainly right for an initial spadework cannot suffice now, in a catastrophic age when we have to return to the roots of viable civilisation in order to have a chance of not losing it wholly. Further, I need to factor in frequent simplifications by hasty readers of that essay; then at least one ingenuous mistake of my own, an insufficient clarity about the horizon of science; and finally, my revisitations of novum in “Where” and “Splitting.”

Concerning my horizon here, I shall limit myself to the indication that semantic forms, with which I started, should be broadened by means of a rich and well-based understanding (political epistemology), and by envisaging application (pragmatics), in a historical feedback.1 What do they lead to in relation to the New as naming, concept (indeed perhaps a topos), and tool for understanding? My hypothesis is very similar to conclusions that it was the failure of the working classes – Marx’s associated producers – to substitute themselves for the State which enabled the old novelties of global mass impoverishment and global warfare (cf. Tronti 123).

I shall start with epistemological grounding for the novum.

1. The Novum within Cognition or Understanding:

… For it is part of my happiness to work at having many others understand what I understand, so that their intellect and desire may accord with my intellect and desire; and in order that this may be, it is necessary to understand nature sufficiently to reach that perfected state, and after that to build such a society, which is to be desired, in which the greatest possible number of people may reach it in the most secure and easy way.

Benedictus Spinoza, De Intellectus Emendatione (Of Bettering the Intelligence)

A basic epistemological presupposition is that any understanding implies a given set of Distances towards what is to be understood and a stance (more or less explicit) that wishes to resolve this distance into articulated and transmissible understanding. Any cognition or understanding, including Newness as a cardinal cognitive area, can only become operative in societal practice when used and found correctable in human spacetime.2

My axioms for cognition or understanding are that 1/ it must be repeatable; 2/ it must be falsifiable by formal logic and historical practice, which means factoring in relevant presuppositions; a central method of falsification is in modern science the experiment; 3/ though in natural sciences the presuppositions are usually very far off, no practical use of the New is only “conceptual” without being at the same time also “emotional” – indeed, this antiquated romantic distinction should be overcome. As I argued long ago, this could be done within a refurbished topology (see Suvin, “Cognitive”), where a quartet, a sculptural frieze, a theater, movie or video performance, a metaphoric system or indeed a personal emotional constellation may be no less cognitive than a conceptual system – though, no doubt, in different ways. Both the conceptual and the non-conceptual ways of genuine understanding might allow people to deal with alternative possibilities, i.e. with not merely or fully present objects and relationships. Obviously there may and will be cognitively empty or banal symphonies, paintings, metaphors, and emotions galore, just as there are concepts and conceptual systems galore with little or no cognitive status: Bouguereau and other pompierriste painters or the Nazi emotions of racial pride are cognitively neither better nor worse than the 19th-Century “sciences” of phrenology or race theory, and the same holds for 20th-Century horror Fantasy or Great Man charismatics vs. sociobiology or “Creation theory,” since all zeros tend to be equal.

The above axioms exclude personal and/or mass hallucinations and conscious hoaxes (e.g. that the human species is divided into races or that competition is the only factor within the humans’ coexistence or that stronger must mean better). Obversely, there are clear limits to understanding in any phase of history, exacerbated in the downward phases such as ours in the last half century. Though we know much more about the universe than a century ago, I don’t believe we know much, while the knowledges about human relationships are systematically slighted. The greatest and most revolutionary breakthroughs, such as Einstein’s, were limited by an a priori belief that “The Lord is cunning but not malicious,” i.e. that we are entering upon operative cognitions about the whole; the same romantic and revolutionary optimism holds for Marx in “human sciences.” No doubt, beginning with empirical phenomena cognition can generalise using the potentialities furthering life. Yet we have seen that the potentialities can be misunderstood, physically blocked or mentally corrupted.

Any concept must be distinct from others, and in some ways closed off toward them, or it is unusable. Any distinguishing and comparing requires entities with a constitutive interval (caesura, break) between them. But in addition, concepts designating the New are intimately connected with the arrow of time, in other words possibilities within history: there is no ahistorical newness, though some novelties last longer; indeed, I would enlist Braudel’s “long duration” to argue that some constant generalities, no doubt much changeable in particulars, are implied in the concept of class society, say war and violence exercised by rulers on ruled. To talk about newness presupposes radically lay time-horizons and value systems dispensing with divine intervention (which was itself either cyclically repetitious as in the Hellenic Zeus and Co., or a New Testament after which there is only the end of time). A novum means that something like it has not yet existed: what had existed is now called the old and defended by conservatives. The New is the present as flowing immediately into a future; for if it were simply an inconsequential item, its impact would be brief (I shall return to this in section 3.2). No concept can be set up as a hunter’s trap in the forest, rather it indicates that a new ecology of the area is possible.

The New is also opposed to tradition, which etymologically means that which has been handed down to us by past generations. As T.S. Eliot told us in “Tradition and Individual Talent,” tradition then has to become dynamic: it can incorporate the valuable novum. Sociohistorical dynamics can be seen as the formal precondition for a proliferation of novums.

History becomes noticeable and dominant when changes accelerate: globally after the “discovery of America,” i.e. the unification of the globe by commercial capitalism; in Europe after the Napoleonic wars (cf. Lukács). The revolution in the Buddhist and Latin-cum-Medieval sense of revolving while biting its tail is here discarded; in its Jacobin and Bolshevik sense, revolution is a new dispensation dawning for mankind. True, the globe is by now bounded as a more and more known space, but history becomes a three-dimensional field whose depth is The Unknown, as identified by the best of English and French poetry – Shelley, Baudelaire, Rimbaud…: “Au fond de l’Inconnu pour trouver le nouveau” (Into the depths of the Unknown so as to find the new),

Imaginatively, this is an arrow (downwards or into the future), a one-dimensional system. Yet already in the richer model of a two-dimensional system, the two Cartesian axes which are in this case duration and value, the resulting curve of the novum can be bent into all kinds of zigzag or sinusoid shapes, axiologically upwards and downwards. In three dimensions and all the new spaces opening up, say in algebra after the mega-novum of the zero, no holds are barred, just as they never were in profiting: we can have a Hegelian spiral progress through oppositions (which Marx adapted with the key amendment “once we got rid of capitalism”) or the never-ending booms and busts of stock-market capitalism – or indeed the crises of economics and the mega-catastrophes of imperialist warfare, up to the horizon of Nuclear Winter and/or ecological collapse. The disalienating Good for humanity, the eutopian horizon, is in principle as possible as the dystopian awful warning that it may fail or the antiutopian glee of Social Darwinism, where Man is red in tooth and claw and the laggard are thrown to the wolves. The future of hope can become a past future (cf. Koselleck’s semantics). The New can be fertile or murderous: Swift’s Giant King is struck with horror at the invention of gunpowder and “secrets of State,” as opposed to “making two ears of corn to grow upon a spot of ground where only one grew before.”

Thus, I wish to preserve the sense of “cognition” as understanding better, not only more quantity but also human liberatory quality. Yet we then have to concede that capitalism has bent cognition towards murder: as in Brecht’s great poem 1940, from which I translate one fragment:

Out of buzzing libraries

Step the butchers.

Clasping children to them

Stand the mothers and search aghast the skies

For the inventions of the scientists.

Summing up: in this new dispensation, history means, as of the Industrial and French Revolutions, an unprecedented multiplication of working people and their subsumption under either of capitalism’s Janus faces: inclusive citizen and grasping bourgeois, Rousseau and Gradgrind. The novum, itself a handy new denotation of Ernst Bloch’s, addresses the sudden, unforeseen, and surprising irruption of heretofore unknown factors with a more or less lasting impact; it was spelled out first most clearly in the arts and philosophy, but then later adopted by capitalist technology as the essence of competition. The term names a useful fusion of particular units in duration (diachrony, syntagmatics) with a generalising term in overview (synchrony, paradigmatics). But there is no guarantee the novum will be used for better rather than worse lives for persons and large human groups.

2. A Look Backward: Some History of the Novum Term:

Reculer pour mieux sauter: vivid French idiom for going backwards in order to jump forward better.

“What’s new?” is an interesting and broadening eternal question, but one which, if pursued exclusively, results only in an endless parade of trivia and fashion, the silt of tomorrow. I would like, instead, to be concerned with the question “What is best?” a question which cuts deeply rather than broadly, a question whose answers tend to move the silt downstream.

R.M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

In these last years I have put almost all my papers and books in English onto three internet sites that daily send me notifications where are they cited, and I sometimes look a fraction of them up. Yet after reading quite a number of such articles or dissertations, I feel I should clarify three points about the novum within three evolving essays of mine. To remedy the strong pressures of our age to either forget or caricature the past, I may have to repeat some of their arguments.

The first point is a complaint, the second admits I had an insufficiently differentiated approach, and the third advances to political epistemology.

2.1. Against Decontextualisation:

A strange feature found in many colleagues’ uses of my novum I shall call decontextualisation. The great number of citations testifies how this term has in the meantime become a staple of defining SF. Yet in probably a good majority of instances, what is being cited is one or at best two excerpts from the first pages of my essay “SF and the Novum.” There is little evidence that the following 20 book pages were taken into consideration, and none that the subsequent essay on “News from the Novum,” finally published in 1997 as “Where,” was looked at. True, some of the major discussants of SF and utopian theory, such as my comrades Fredric Jameson, Tom Moylan, and Phillip Wegner,3 have amply and ably commented on my writings, which might compensate for my following peeve. Indeed, it does axiologically, but I doubt it does politically.

In particular, the use of novum has only too often become disjoined from, first, the whole section 3 of the first essay, “The Novum and History.” At its outset, I stressed that “[t]he novum … is not fully or even centrally explained by such formal aspects as innovation, surprise, reshaping or estrangement, important and indispensable though these aspects or factors are. The new is always a historical category … determined by historical forces which both bring it about in social practice (including art) and make for new semantic meanings that crystallise the novum in human consciousnesses….” (80) Within history, I opted for a polarising axiological relevance to the reader:

In view of this doubly historical character, the SF novum — born in history and judged in history — has to be differentiated not only according to its degree of magnitude and of cognitive validation… but also according to its degree of relevance…. Not all possible novelties will be equally relevant or of equally lasting relevance from the point of view of, first, human development, and second, a positive human development. (81)

I concluded upon the traces of Bloch by opposing “the yearly pseudo-novum of ‘new and improved’ (when not ‘revolutionary’) car models or clothing fashions to a really radical novelty such as a social revolution and change of scientific paradigm making, say, for life-enhancing transport or dressing…” – that is, for “human relationships so qualitatively different from those dominant in the author’s reality that they cannot be translated back to them merely by a change of costume. All space operas can be translated back into the Social Darwinism of the Westerns and similar adventure tales by substituting colts for ray-guns and Indians for the slimy monsters of Betelgeuse.” (81-82)

Second, my ending and telos for the discussion of the novum was centered on freedom as “the possibility of something new and truly different coming about, […so that] the distinction between a true and fake novum is … not only a key to esthetic quality in SF but also to its ethico-political liberating qualities.…” Finally, I pointed to

the bedrock fact that there is no end to history, and in particular that we and our ideologies are not the end-product history has been laboring for from the time of the first saber-toothed tigers and Mesopotamian city-states. It follows that SF will be the more significant and truly relevant the more clearly it eschews final solutions, be they the static utopia of the Plato-More model, the more fashionable static dystopia of the Huxley-Orwell model, or any similar metamorphosis of the Apocalypse…. (82-83)

To decontextualize a definitional snippet brings about a loss of historical situating that indicated when and how to properly use a term.

Let me underline that my stricture against decontextualisation is not meant to be a simple peeve or personal blaming of a number of younger critics and scholars. I would rather blame the more and more starved, “tight money” and alienating, educational systems through which they had to wend their way. Professionals now have to do a lot in a hurry and without proper intellectual leisure for reflection and reading. Also, a devolving capitalism enforces a “cellular phone” mentality focussed on immediate point-like entities in an anxious present: the only context left is the implicit idol of market financial value.4

Cognitively, however, as my teacher Brecht put it, the stone does not excuse the fallen.

2.2. On the Novum and Scientific Method:

2.2.1. The Spoor

In “SF” I posited the novum as “postulated on and validated by the post-Cartesian and post- Baconian scientific method. This does not mean that the novelty is primarily a matter of scientific facts or even hypotheses….” I inveighed against using here scientism and natural sciences as the model, insisting that all science was and always has been a historical category, so that I rather spoke of a “methodically systematic cognition.” I even identified some relevant scientific methods such as:

the necessity and possibility of explicit, coherent, and immanent or non-supernatural explanation of realities; Occam’s razor; methodical doubt; hypothesis construction; falsifiable physical or imaginary (thought) experiments; dialectical causality and statistical probability; progressively more embracing cognitive paradigms….

From the widening cognitive horizons, it followed “that science has since Marx and Einstein been an open-ended corpus of knowledge, so that all imaginable new corpuses which do not contravene the philosophical basis of the scientific method in the author’s times (for example, the simulsequentialist physics in Le Guin’s The Dispossessed) can be used as scientific validation in SF” (67-68).

My whole approach to the novum was based on a conscious decision, matured when studying Brecht, to substitute for Science Fiction a cognitive (but also estranging) fiction. True, I was and am unwilling to simply concede science as a notion to a capitalism that had swallowed it whole, as the Wolf did with Red Riding Hood’s grandma; I thought that, with the help of an armed Hunter, grandma could be gotten out of the belly of the Beast again. But I optimistically failed to ask how come Science as an institution had not opposed its takeover by and channeling into imperialist World Wars – where I would claim an exception for the antifascist aspect of World War 2; thus I let stand in “SF” some imprudent traces of the admiration that the Communist Manifesto had accorded to the bourgeoisie. Two sentences may be a useful example: “Thus science is the encompassing horizon of SF, its ‘initiating and dynamising motivation. I reemphasise that this does not mean that SF is “scientific fiction” in the literal, crass, or popularising sense of gadgetry-cum-utopia/dystopia.” (67) In spite of the disclaimer in the second sentence, the first one was wrong and could have misled the hasty readers.

Thus, in my second essay “Where,” in 1996-98, I proceeded to doubt at length monolithic implications of the novum, to begin with in SF. I noted that SF makes sense by referring to the readers’ here-and-now through not referring to familiar empirical existents but inventing new terms for strange possibilities: many salient textual existents are empirically non-existent Newnesses; the resulting novum may be (should be) fun in itself, but it is valuable because it nudges the readers to rethink their familiar and apparently natural givens – their imaginary encyclopedia. I realised by then that, after the Post-Modernist and capitalist Deluge, formalism, much needed before the mid-1970s, when intellectuals could count on mass antiwar and anticapitalist movements – was not enough. It became clear that epistemology cannot understand any X, including a novum, without asking the political question “what for?” – in the interests of which large societal groups (such as classes of people) does X function and how. Such a political epistemology would then be following two generational waves of SF: Bill Gibson or Pat Cadigan or Octavia Butler or Marge Piercy or Stan Robinson, who showed us how Dick’s Palmer Eldritch or Debord’s addictive image-virus is reproducing within all of us, manipulating our takes on reality: “The scanning program we accept as ‘reality’ has been imposed by the controlling power on this planet, a power primarily oriented towards total control,” said the pioneering William Burroughs (Nova 51, cf. also Naked).

Against such alienation and decontextualizing, I realised that we needed to roughly identify what Atlantis collapsed in the Deluge and why. To begin with, the loss of strategic hope, of the horizon of a classless society, meant we shall in the 21st Century have scores of dirty wars, a deranged climate, and serious food and energy starvations. Further, most of SF had by the 1990s been snatched by the corporate conglomerations of Hollywood, TV, and the mega- middlemen of the book trade – publishing houses, distributors, bookstore chains. US SF in Fordism was rendered possible and shaped by the double market in competing genre pulps and paperbacks, and alongside much perishable stuff there was room at the top for a strong stress on the story’s horizon’s – on what qualitative meanings were being produced, not simply on financial profit. Once the Cold War competition with what was perceived as the Left had ended, money for culture grew tight. This left the field open to a total bottom-line compulsion for “not simply trying to make a profit, but as much profit as possible,” as Joanna Russ wrote. Post- Fordism is dominated by circulation (sales, marketing, advertising), tied into the movie and TV (later video and so on) branches of vertically integrated corporations, which led to increased government as well as middlemen censorship. Such an oligopoly tended to disempower thoughtful editors and force upon us – in tandem with decaying youth education and a mass yearning for quick fixes – Fantasy, militarist SF, and sequels-cum-series as well as the low standards of bestsellers and most SF movies or comics. On the other hand, opposing the suppression of thoughtfulness, there were the bright spots of most SF by and about women and of other brave new names, mentioned earlier.

2.2.2. The Finding

In a global yawning devolution of capitalism as a social formation, the gap between the rich “North” and the poor “South” of the world system doubled from 1960 to 1992, with the poor transferring more than $21 billion a year into the coffers of the rich. This dire poverty gap between classes and nations meant that already in the mid-1980s some 40 million people died from hunger each year, while in 1996 about 1,300 million people were chronically malnourished. Our societies were being turned into crass two-tier edifices, where only a small minority in the North had enough food and energy, or adequate medical care and education, as opposed to the dispensable poor. Human groups divided into resentful islands who do not hear the bell tolling; the “absolute general law of capitalist accumulation: accumulation of wealth is at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil, slavery, ignorance, brutality” (Marx, Selected 483), has been confirmed in spades. No wonder SF was getting contaminated by sorcery and horror: we live in a world of capitalist fetishism run wild, against which Lovecraft’s Cthulhu entities are naive amateurs.

In my essays, I tackled the strong signs of not simply a wrong use of an in itself good science, but of a degeneration of science as a powerful social institution and, willy-nilly, major political force and pressure system. In the scientists’ professional lives – not to speak of the engineers – it enforced narrow specialisation that wiped out civic responsibility for knowledge and its insertion into production, amounting to oblivion of, and therefore practical agreement with, the capitalist hegemony. It became apparent that the only sane way to see science, the world’s leading cognitive structure but also a macro-metaphor and historically constituted collective practice of power, was not as the Messiah but as Goethe’s two-souled Faust. Science as we know it in the last 200 years is a battlefield of “the productive forces of labour and the alienating and destructive forces of commodity and capital” – of cognition and exploitation (Mandel 216, and see Feenberg 195 and passim). This entails on the weak side the uncritical use of unexplained axioms: e.g., for any philologist it should be clear that the concept of “scientific law” has been in Europe adapted from political logos or lex, with all its aporias of mastery.

I was trying to get at this with my early distinction between true and fake novums: but was this enough? What followed when “[t]he key innovation is not to be found in chemistry, electronics, automatic machinery …, but rather in the transformation of science itself into capital” (Braverman 166), and the avant-gardist strategy of innovation at any price became the paradigm of dominant economic practice? “Now everything is new; but by the same token, the very category of the new then loses its meaning…” (Jameson 311). And I concluded that at a minimum the incantatory use of the novum category as explanation rather than formulation of a key problem has to be firmly rejected. Novum is as novum does: it does not supply justification, it demands justification.

In sum: we need radical novums only. By “radical” I mean, as Marx did, a New irreducible to profiting, in critical opposition to degrading relationships between people – and also, in a fertile relation to both a radical break in the future and memories of past humanised oases (Bloch’s Antiquum). Formally, this will be a new genus of novum, as in the best of modern physics or biology, rather than a new species of what was heretofore dominant. Yet here too one should be very aware of the possibility of cooptation, of a fake radicality fusing the worst features of all class societies, most perfectly embodied in the Nazis and now returning in Fascism 2.0.

2.3. Towards an Epistemology of Science: Polarising the Notion:

Still, science is too important, both as political fact and axiological possibility, to be uncritically embraced or refused. I shall argue that, even based on foreshortened situating, texts outside of institutionalised science could scarcely be “scientific” – but they could and should be helpful understanding, i.e. cognitive.

Applied scientific mass production first came about in the Napoleonic Wars, and the novums of institutionalised science have a huge stake in war, in killing and maiming people. The popular emblem of SF, the large space rocket, was developed and used mainly by competing genocidal armies. Science as institution has grown to be largely a cultural pressure-system legitimating and disciplining the world’s cadres or elite, in unholy tandem with the converging pressure-systems disciplining and exploiting the less skilled workforce, usually through sexism and racism (this has been exhaustively rehearsed from Max Weber through Lewis Mumford to the better Frankfurters, and cf. Wallerstein 107-22). It has been largely subsumed into the economy of overripe capitalism, whose systematic dependence on weapons production as well as on strip-mining human ecology for centuries into the future shapes a productive system efficient in details but on the whole supremely wasteful, irrational, and bearing death for millions of “lower” people. Finally, the elite enthusiasm for bureaucratised and profit-oriented rationalism engendered an understandable (if wrong) mass mistrust and horror, reviving most numerous alienations and irrationalisms, and incidentally downgrading SF into a nostalgic precursor of a Fantasy mainly complicit with everyday horrors.

I therefore proceeded to explore on the divorce of wisdom and knowledge, Science1 vs. Science2 (e.g. in “Horizon”). To base novums on formal innovation as hegemonised by modern science grew quite untenable after its overarching novum became the transformation of Science2 into capital: and clearly so when it was force-fed by much Rightwing money into “hard” SF, the “space cadets” of imperialist warfare.

Politically speaking, what if science is a more and more powerful engine in the irrational system of cars and highways with capitalism in the driving seat heading for a crash with all of us unwilling passengers – what are then the novums in car power and design? How can we focus on anti-gravity, or at least rolling roads, or at the very least electrical and communally shared cars – remember the useful tramways destroyed by the automotive industry? How can we constitute a power system able to decide that there can be no freedom for suppressing people’s freedom?

But when I considered the hugely growing exploitation and mortification of billions of working people, a suspicion also grew in my mind that the novum – the surplus or newly created knowledge – was finally anchored in the extortion of surplus or newly created value from the labourers. To the extent that this may be true, it is poisoned or at least rendered ambiguous at the source.

In this context my priority would be food and shelter for the body and the mind of all, simultaneously a novum and an antiquum; this includes a strong focus on cognition or understanding. As to specialised or institutional science, I could not care less whether an SF (or any other) text was such or not, though I much admire judicious reappropriation.

3. Namings: On the Uses of and Discrimination within the New:

[W]e must try to understand what is threatening to kill us off as fully and clearly as we can….

Dorothy Dinnerstein, The Mermaid and the Minotaur

Accumulate! Accumulate! That is Moses and the prophets.

Karl Marx, Das Kapital

Any naming presupposes an identity of being in historical time, a general genus within which differences of species are needed for comparisons. I shall attempt to approach this, for clarity, in a further polarising differentiation concerning the uses of and discrimination within newness.5 This is the domain of linguistic and societal pragmatics, of particular situations in which language or other signifying systems and even actions are used to get things or perform actions.

3.1. Innovation:

This term is most frequently correlated to and acquiescing in sciences and technologies for which capitalist financing and freedoms, including its massive and capillary limits and exclusions for deviants, were the decisive presupposition.

Historically, the novum – and newness or being new – as a topos had implied from the Renaissance on the concept and battle-cry of Progress, which translated the experience of its enablers, the European wayfarers out of the closed medieval world into new and unknown dimensions, thought of as a better future. The great advance of merchant capitalism was to accept the City of Man and not only of God as in Middle Ages, i.e. people as active discoverers, inventors, and pleasure lovers. I do not propose to let go of possibilities for such progress (with a small p), in the meaning of less alienated lives for more people: the names of epoch-making inventors, such as Leonardo, Gutenberg or Newton are still our Great Ancestors. The advance politically culminated in the French Revolution, and within art in the Romantics. In Hegel’s late lectures on esthetics art is treated as a vision of the universe – first in painting and then in poetic language – that can conciliate horror and fear with acceptance of the City of Man. His example was the romantic tragedy (Schiller), and he was enthused by the confrontation and permeation of esthetics and understanding; Lukács drew from here the rise of the novel as opposed to the chivalric verse epic.

But the young and dewy-eyed bourgeoisie, best described and eulogised in The Communist Manifesto of 1848, has since devolved into and become consubstantial with growing capitalist and State violence (let us recall Braverman’s encapsulation in 2.2). This was argued as a new historical phase in Luxemburg’s economics and pinpointed for politics in Lenin as a new phase of destructive imperialism. After an atypical phase of the glorious Welfare State, to which I shall return, this devolution has as of the mid-1970s monstrously grown into perpetual warfare with assassination of hundreds of millions as well as expanding subjection of billions by surveillance States. The New was mainly channeled into innovation within capitalist technology and management, with some exceptions in the marginalized arts.

The upshot of this catastrophic occlusion of historical possibilities was most clearly summarised at the beginning of the Second World War by Walter Benjamin’s denial of Progress as a meaningful category: the New was no longer the Humanly Better; to adapt Nietzsche’s apt term, it was largely inimical to life (lebensfeindlich). Mainly, the use of the New was uncritically praised by natural sciences (and then by societal sciences attempting to ape the mathematised ones in order to get financed) and old capitalist profiting; this led to an increasingly cynical realisation that the novum may in itself be axiologically neutral. Both these uses can be seen in Thomas Kuhn’s famous “scientific revolution” or new paradigm for understanding how to cope with the world (cf. both his Structure and essays in Essential). The Kuhnian “essential tension” between tradition and innovation leads to a focal distinction between normal and extraordinary phases of culture. These phases are within chronological history but “incommensurable.” For Kuhn, History is largely bereft of causes and values, so that his terms such as normal and extraordinary – or indeed “revolutionary” – are common-sense axioms. Still, his sly denomination of “extraordinary” is associated with upheaval and more frequent change, evident in scientific innovation. Any criteria outside the history of institutionalised science since the European 17th Century are deemed irrelevant (to the contrary, I argue in “Horizon” that “science” itself became an ambiguous term, subject to radical axiological change). Later on, Kuhn expressly repudiated sociopolitical factors even for acceptance of scientific novelties,

Yet in fact innovation has in the following 60 years’ eruption of supercapitalism become the favourite God-word of uncounted capitalist corporations and satellite societal sciences. A “savage innovation with no rules, no limits, a lay cult of the new that advances, whatever the social costs,” dismantled the Welfare State (Tronti 119) and its compromise between capitalist strategic power and sizable concessions to working people in salaries, pensions, public health, and similar, making life easier for a large majority of people. These concessions were revealed to be a simple defanging of popular threats inside capitalism, brought to a head by Lenin’s establishment of the Soviet alternative, by the Great Depression of 1929-33, and by the (then) too costly fascism. This is why they could from the mid-1970s on be systematically withdrawn in the Thatcher-Reagan turn to the Right of the ruling class, with a return to Hobbesian wolfish market ideology. Solidified ever since by banks and tanks, this has spread into every corner of a globalized world, including failed Russia and the relatively thriving China. It has grown into a religious dogma, deviations from which are punished by starvation (e.g. in Syriza’s Greece) or if need be naked warfare: by banks or tanks. Here the New practically means what brings more profit and with it stock-market prestige and political influence.

For discussing disalienating, friendly-to-life novums, innovation can therefore only be used satirically, by contraries. We should rather remember our communist Great Ancestor William Morris, who already by the end of 19th Century longed for “an epoch of rest.”

3.2. On Semantic Neutrality with Pragmatic Differentiation:

In 2018 I returned to the novum in an essay (“On Splitting”) that tried out an axiological splitting of concepts – in particular, for communism and SF – to opposite poles of a spectrum. To my mind, semantic neutrality is a necessity in social discourse in which longstanding contraries of value and horizon coexist – as they do in a mass society of industrial and post-industrial capitalism (already discerned by Marx in my first epigraph). This applied in spades, I argued, to our devolving times (even before the double turn of the screw towards a powerfully autocratic “security society,” arriving with the shocking opportunities of the “coronisation” pandemy and then the war in Ucraine). It was always one matter to digest a perceptual-cum-cognitive shock, another to pass from an understanding to effecting change; but now, as Gramsci first remarked, many barriers were put into place to hinder this passage.6

Historically, the difficult leap into possibility has often been aborted. Example: the Neolithic “agricultural revolution,” extending from the Mediterranean shores to China, failed to take root among the tribes of ancient Australia, possibly because it was wedded to private rather than community property. Therefore, in good pragmatics, i.e. in all particular cases, a sociopolitical and historical examination is needed, beginning with situating the intended and the real addressee and user of any particular cognition. Centrally, the barriers for instituting a novum are either ecological or strictly economico-political; in the latter case, the barriers are proportional to the rulers’ fear of losing power and profit.

I concluded that novelty or the New had deliquesced into a stream of sensationalist effects mainly serving to replace existing commodities for faster profit. The rulers’ withdrawal of the Welfare State led to an exponentially growing disbelief into livable human futures, a breakdown of civil life confounding sweeping eutopianism (e.g. Bloch’s) when faced with tens of millions of unnecessary deaths among the politically weak classes, huge destruction of our common environment, and more hugely destructive wars. Should the position of a provisional survivor be that if there’s no dry land left, and if God and Communism are dead, then everything is permitted? Or is it rather, how many arks of what kind do we need, what group could build them how, and in which direction may the dove look for shores?

A rejoinder to rising disempowerment, exploitation and psychophysical lesions of hundreds of millions could only be, as argued above, radically liberating novums. They would enable us to understand and act against the rising tide of anti-life militarism, racism, sexism, and other discriminations whose horizon is fascism 2.0, fed by central commandment of capitalism: profit now, more and more profit. A pioneering SF counter-example was Heinlein’s super-racist united humanity of egalitarian super-militarists in Starship Troopers, and then the eponymous movie: economics were suppressed and genocidal discrimination transferred to non-human Bugs – read: the dangerous classes or radical rebels.

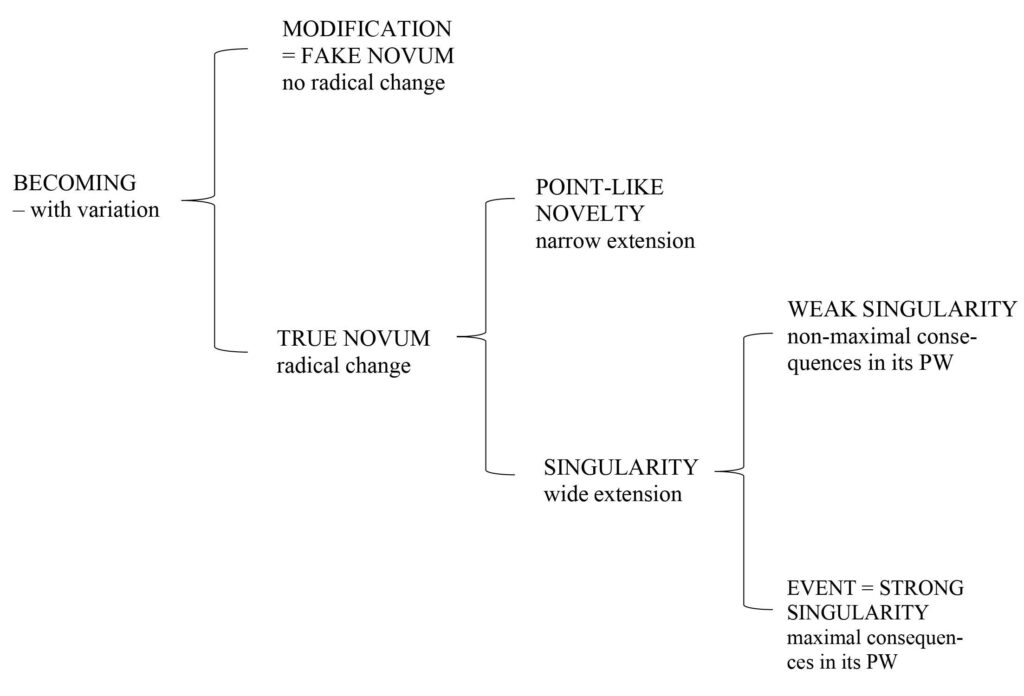

However, a radical renovation cannot nowadays be monolithic but differentiated, “an ambiguous utopia” (Le Guin), admitting pragmatic nuances and subcategories. Therefore, stimulated by some Badiou, I reshaped the possible varieties of the novum in a sequential fashion based on pragmatic impact and a Possible World approach. The result was a Cascade Sequence of Novums:

Discussion of the Graph (with examples)

FAKE NOVUM: Easy: more powerful and faster machines to kill and maim people – as all military technology – or to destroy nature; all private cars even if they have AI. Or. the capitalist innovation with glitzy surface variations simulating novelty – such as chrome tailfins on cars in the 1950s or NGOs pushing “civil society” in Eastern Europe of the 1990s.

TRUE NOVUM: Collective means of transport with minimum possible destruction of nature: armies without weapons to destroy people and nature but intervening usefully into relationships between people and with nature, as explained by Charles Fourier and Fredric Jameson.

POINT-LIKE NOVELTY: Truly useful but only for a relatively limited purpose – find your own examples.

WEAK SINGULARITY: A true and widely applicable novum but with limited consequences for its Possible World concerning only some sectors, trades or groups – say, nylon stockings. This is probably connected with compromise formations, such as Obama’s initial healthcare proposals (anyway torpedoed because too near to a True Novum).

STRONG SINGULARITY, Badiou’s EVENT: All true novums as inventions significantly benefitting potentially everybody and/or the human habitat as a whole – or at least a strategically large and growing part of either – and having no major negative consequences: say, invention of printing or of vaccines.

Two mega-events belong here: first, the invention of human solidarity for all working people, as suggested early on by rabbi Yehoshuah’s solidarity within his communism of love and then by the French and Bolshevik revolutions (both soon squelched and perverted). To safeguard and perpetuate solidarity, an institutionalization of Power is today needed going from working people upwards and controlling the momentary government in all plebeian revolutions; they were called Soviets in Russian, Räte in German, and I’m not sure what by the EZLN in Chiapas. Second, electricity, popularly also rightly called light: without light, no Enlightenment. The two were fused in Lenin’s formula for introducing communism to backward 1920s’ Russia: “Soviet Power and Electrification of the whole country.”

The only possible emergence from our Deluge I can see is the mega-event of communism in Marx’s sense – the abolition of power based on the exploitation by classes of rulers over everybody else, True, we would today have to add several further factors to Lenin’s foundations: yet let us remember he was the only statesman I know of in history who opted out of a huge war. The major novum to be desired today, as a radical opposition to war and Fascism 2.0, would be a Leninism 2.0, relating to him as Einstein did to Newton: a strong singularity.

Notes

1. I shall dispense with all but the indispensable referencing. In the internet age, anybody can find the references to Benjamin’s denial of Progress, Kuhn’s paradigms or Jameson’s utopian army in a few minutes. This is accompanied by referring more than I’d like to my earlier works, written in a less catastrophic age and heavily referenced, and using the terms “I” or “mine” with unpleasing profusion. Still, I hope this essay may have cognitive value beyond the personal.

All unreferenced translations are mine.

2. As to other critiques mentioning the novum I have happened to see in print or on internet, I have valued those by Tom Shippey, Gerry Canavan, Allison Hegel, Eric Picholle. Eric D. Smith, Patricia McManus, and Antonis Balasopulos.

3. This is not to deny the existence of dissent to my approaches early on. Its strongest expression might be a long encyclopedia entry by my contemporary Peter Nicholls. While his basic position may be defensible, though I think it is insufficient, his implication that I require “that the novum be explicable in terms that adhere to conventionally formulated natural law” is a sterling example of misreading my intention, that much pushed me toward section 2 of this of essay.

4. I do not develop here a general hypothesis for cognition, which I gingerly approach in “Little.” However, its undoubted basis, the much-debated perception, is as a rule co-shaped by the personal and collective perceiver-subject; it includes attention, pre-judgements that easily grow into encrusted prejudices, and even provisional hypotheses, cf. Helmholtz and Allport.

5. Many pioneering examples for such a fusion, that also presupposes value choices or axiology, could be found. Here are two: in general, the opus of Karl Marx, such as the Grundrisse and Das Kapital; in particular, the opus of A.N. Whitehead, from Adventure of Ideas to Science and the Modern World (within the novum field he favours the term of creativity, and as a name for his writings – just as Montaigne and Brecht – he favours essay).

6. The first part of my discussion of SF in that essay argued that, in retrospect, estrangement was also a neutral and bipolar term, akin to Shklovsky’s perceptive or esthetic ostranenie; Brecht Verfremdung then used it for a critical and disalienating politics (see a meticulous account in Moylan, and a long later discussion in my “Parables”). A Rightwing estrangement, practiced in 20th-Century literature say by Hamsun, Jünger or the latter Pound, can very well be wedded to various proto-fascist myths.

Works Cited

Allport, Floyd. Theories of Perception and the Concept of Structure. Wiley, 1955.

Braudel, Fernand. “La longue durée.” Annales: Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations 13.4 (1958): 725-753, www.persee.fr/doc/ahess_0395-2649_1958_num_13_4_2781, Accessed May 15, 2022.

Braverman, Harry. Labor and Monopoly Capital. Monthly Review P, 1974.

Burroughs, William S. Naked Lunch. Grove P, 1959.

—. Nova Express. Grove P, 1964.

Eliot, T.S. “Tradition and Individual Talent,” rpt. in his Selected Essays, 1917–1932. Faber & Faber, 2009.

Feenberg, Andrew. The Critical Theory of Technology. Oxford UP, 1991.

Helmholtz, Hermann von. Handbuch der physiologischen Optik. Voss, 1867.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke UP, 1991.

Koselleck, Reinhart. Vergangene Zukunft. Suhrkamp, 1988.

Kuhn, Thomas S. The Essential Tension. U of Chicago P, 1977.

—. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. U of Chicago P, 1962 (2nd edn. 1970).

Lukács, G[eorg]. The Historical Novel. Transl. H. and S. Mitchell. Beacon P, 1963.

Mandel, Ernest. Late Capitalism. Transl. J. de Bres. Verso, 1978.

Marx, Karl. Selected Writings. Ed. D. MacLellan. Lawrence & Wishart, 1977.

Moylan, Tom. “Look into the dark: On Dystopia and the Novum,” in P. Parrinder ed., Learning from Other Worlds. Duke UP, 2001, 51–71.

Nicholls, Peter. “Fantasy.” Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. https://sf-encyclopedia.com/ entry/fantasy Accessed Oct. 15, 2019.

Suvin, Darko. “”On Cognitive Emotions and Topological Imagination.” Versus no. 68-69 (1994): 165-201.

—. “On the Horizons of Epistemology and Science.” Critical Quarterly. 52.1 (2010): 68-101.

—. “A Little Liberatory Introduction to Talking about Knowledge.” Historical Materialism blog, Jan. 7 2022, www.historicalmaterialism.org/blog/little-liberatory-introduction-to-talking-about-knowledge

—. “Parables and Uses of a Stumbling Stone.” Arcadia. 5.2 (2017): 271–300.

—. “SF and the Novum” (1977), in Metamorphoses of Science Fiction. Yale UP, 1979, 63-84.

—. “On Splitting Notions: Communism, Science Fiction,” in Disputing the Deluge: 21st Century Writings on Utopia, Narration, Horizons of Survival. Ed. Hugh O’Connell. Bloomsbury Academic, 2022, 245-55.

—. “Where Are We? How Did We Get Here? Is There Any Way Out?: Or, News from The Novum” (1997-98), in Defined by a Hollow. P. Lang, 2010, 169-216.

Tronti, Mario. Noi operaisti. Derive Approdi, 2009.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. Geopolitics and Geoculture. Cambridge UP, 1992.

Darko R. Suvin, scholar, critic and poet, born 1930 critic and poet, born 1930 in Zagreb, Yugoslavia, is a Professor Emeritus of McGill University and Fellow of The Royal Society of Canada. He was a co-editor of Science-Fiction Studies, editor of Literary Research/Recherche littéraire, visiting professor at 10 universities, has won various awards and scholarships and prizes for poetry. He has published 35 book titles, edited 14 volumes, and written hundreds of articles on literature and dramaturgy, culture, utopian and science fiction, political epistemology and communism; also three volumes of poetry. Vita and essays are accessible at www.darkosuvin.com; papers to read and download at https://independent.academia.edu/DarkoSuvin/Papers

[Volume 5, Number 1, 2023]